Who or what are the most significant influences on your musical life and career as a composer?

One of my earliest experiences with music was when I was about six, sitting at a friend’s piano. I found I could pick out simple tunes by ear, even though I’d never had a lesson. It didn’t feel like a revelation at the time — more like something familiar I was reconnecting with. That early sense of music being something instinctive, rather than something you had to force, has stayed with me throughout my life.

Later on, private lessons with George Hadjinikos — who had studied with Carl Orff and was a major figure at the Royal Manchester College of Music — really changed everything for me. He showed me that music wasn’t just about precision or tradition; it was a living, breathing language, something you had to respect, of course, but also be willing to challenge. Hadjinikos had this wonderful way of opening doors without ever pushing you through them — he gave you the space to discover for yourself just how limitless music could be. Those lessons became a real foundation for me.

At some point, I realised that the music we create is really only ever a blurred reflection — a glimpse — of something much greater, a kind of underlying composition that sits behind everything. Chasing that feeling led me to all sorts of music, listening not so much for style, but for the hidden threads that connect it all.

Certain composers became companions along the way. Beethoven showed me how structure and emotion can fuse into something truly timeless. Frederick Delius taught me how even the lightest orchestral touch can carry immense emotional weight. Steve Reich revealed how repetition can stretch and shift time itself, creating breathing textures. John Coltrane brought a spiritual urgency to music — it became something necessary, almost like prayer. And Iannis Xenakis, through his fearless use of electronics and mathematics, pushed sound into something raw, elemental, and profoundly human.

Looking back, it’s never been just one teacher, or one composer, or one moment. It’s been a slow unfolding.

What have been the greatest challenges of your career so far?

One of the biggest challenges for me — and it’s still ongoing — has been trying to forge a truly unified musical language out of a lot of different impulses: traditional technique, the unfolding processes of minimalism, electronics, and modern contemporary music. And doing that without any one element feeling like it’s just been tacked on. For a long time, I wrestled with self-doubt, questioning whether my ideas could be both coherent and genuinely boundary-pushing. Over time, I’ve learnt to turn that inner critic into more of a creative partner — its questions sharpen the work, but they don’t stop the music’s own momentum. That ongoing dialogue between unity and exploration continues to shape and energise everything I write.

What are the special challenges/pleasures of working on a commissioned piece?

Every new project has its own challenges. It’s a chance to step outside yourself a bit, to listen more closely, and to explore things you might not have found otherwise. When you’re working on a commission, you do have to put your own ego to one side. It’s not just about what you want to say — it’s about responding to something bigger, whether that’s a space, a story, or an idea. And often, that’s when you end up discovering new parts of your musical voice. At the same time, there’s a real pleasure in the structure that a commission gives you. Having a clear deadline and a framework to work within can be surprisingly freeing — it sharpens your focus, helps you make choices, and often opens up new creative possibilities you might not have found otherwise.

What are the special challenges/pleasures of working with particular musicians, singers, ensembles or orchestras?

Every musician, every singer, every ensemble has their own instinct, their own way of breathing life into the music. One of the real challenges — and one of the great pleasures — is learning how to meet them where they are. It’s not simply a case of giving clear instructions. It’s about finding ways to spark their imagination, so they’re not just playing the notes, but really inhabiting the music. I always try to leave enough space for them to bring something of themselves into it, while still keeping us all moving toward the same vision. When that connection happens, the music becomes something much richer and more alive than anything you could have planned entirely on your own.

Of which works are you most proud?

I don’t know if “proud” is exactly the word I would use. It’s more a sense of quiet fulfilment when something feels true to what it set out to be. If I had to choose, I would say C’est beau, my latest work for a contemporary dance performance at the Paris Cultural Olympiad 2024. It was inspired by the poetry of Baudelaire—the way he captures beauty in fragility, contradiction, even decay. I wanted the music to live inside that tension—fragility and chaos coexisting, but without any grand, sweeping gestures. The piece unfolds through small motifs, subtle shifts, and silences, with strings, clarinet, piano, and soft electronics creating a breathing, intimate space. With C’est beau, I feel I stayed true to the spirit of the project: exploring beauty not as something polished, but as something wounded, vulnerable, and human.

How would you characterise your compositional language?

I would say my musical language is about searching for unity through contrast. I’m fascinated by the space between structure and freedom, between acoustic and electronic sounds, between something ancient and something modern.

Sometimes my music moves in simple, clear lines. Other times it dives into dense textures where order and chaos live side by side. I’m not interested in fitting into a genre—I want each sound, each gesture, to feel necessary and alive. Above all, the music has to carry emotional truth. It has to invite the listener into a space of memory, reflection, and movement.

How do you work?

It really depends on what I’m working on. Day to day, I try to create something — a bar of music, a line, a sound, an improvisation — without thinking too much about whether it’s any good. I’ll record it or jot it down and just archive it. Some ideas I come back to quite quickly, others sit there for months, sometimes longer. Even the scraps that seem a bit meaningless at first often grow into something more substantial over time. That daily practice keeps me switched on and keeps the channel of inspiration open, even when there’s no particular project on the go.

When I’m working on a specific project or a commission, the process shifts a bit. I tend to spend a lot of time just thinking — not necessarily about the music itself, but about what the project is trying to say. I think in terms of images, colours, emotions, atmospheres. I try to let the ideas grow naturally, without rushing to put anything down too soon.

Then, as the deadline gets closer — whether it’s for a recording, a score, or a demo — I sit down and start writing properly, without overthinking. And often, everything I’ve been carrying around — all the emotions, the images, the ideas — seems to find its way into the music, almost as if it had just been waiting for the right moment.

As a musician, what is your definition of success?

Artistically, I think success is about creating a space where music becomes something shared — a moment of real connection between the artist, the audience, and the wider human experience. On a personal level, it’s about staying true to my own voice, keeping a healthy balance with life outside of music, and staying open to growth without losing sight of who I am at the core.

What advice would you give to young/aspiring composers?

Stay curious. Stay playful, like a child. Try to hold onto that spirit, or if you lose it for a while, find your way back to it.

Explore the universe of music with all your being. Technique and knowledge are important, of course. But the real magic comes from staying open—fearless, joyful, and connected to the reasons you fell in love with music in the first place.

What do you feel needs to be done to grow classical music’s audiences?

I think we need to bring classical music closer to people — make it feel less academic, less about expertise, and more about direct emotional experience. It’s about creating spaces where people can come to the music freely, without feeling they have to “understand” it before they can enjoy it. If we put more focus on communication, authenticity, and emotional honesty, I really believe classical music will carry on finding new audiences in a way that feels alive and genuinely meaningful.

What’s the one thing in the music industry we’re not talking about but you think we should be?

I think we don’t talk enough about the need to protect space and time for genuine artistic creation. There’s so much pressure now to produce, to promote, to stay visible — but real work often needs silence, slower rhythms, and the freedom to grow without being forced. I think we ought to have more conversations about how we can protect that space, and how we can help artists stay connected to their deeper voice, rather than getting swept up in all the noise that surrounds the industry.

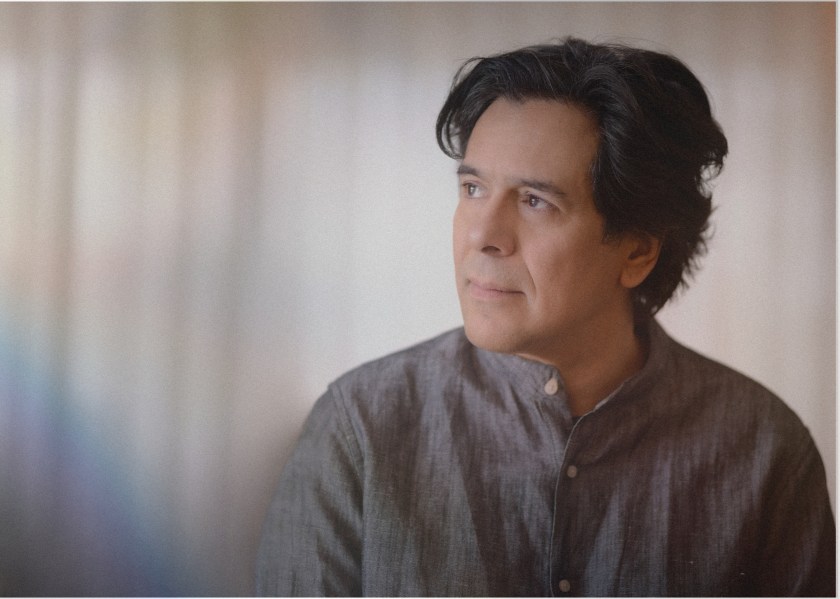

Tryfon Koutsourelis releases his next single from his upcoming album C’est Beau on 30 May

Discover more from MEET THE ARTIST

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.