Who or what inspired you to take up composing, and pursue a career in music?

Growing up, music was playing in our house morning, noon and night. My parents had a record player before they had curtains. At first it was Bob Dylan, The Beatles, The Byrds and a cornucopia of the great Sixties acts, then my dad always hungry for knowledge and new experiences bought home Bernstein conducting Baroque, Mozart, and a St Martin’s in the Field album of Corelli and mornings suddenly sounded different. The record collection grew with the films he was producing; Liszt for Lisztomania, Mahler for the film Mahler, and my love of classical music was shaped by that. From then on I wanted to make music, as beautiful as that I was surrounded by. My path was sealed.

Who or what were the most significant influences on your musical life and career as a composer?

Attending the recording of the operatic part of the score for Stardust, the follow up film to That’ll Be The Day, a full orchestra and chorus were performing Gounod’s Dea Sancta with David Essex singing the lead in a studio in Wembley, a wonderful part of my brain lit up, feeling the power of the ensemble.

Paul Williams was writing the music and lyrics for Bugsy Malone, playing the score on the piano I was being taught on. Watching him showed what was possible and what I wanted to achieve.

I worked with Michael Kamen for a number of years orchestrating his work. He was a huge influence and a giant of a man.

Lastly, but most importantly Vangelis. I was fourteen and went to Vangelis’ house, having recently come under the spell of the synthesiser. Vangelis had an abundance of the latest and best synths, it was heaven. I then visited his Nemo Studios for the recording of Chariots of Fire. Vangelis taught me not just about music, but about life and the role of the artist. I still revere him today.

What have been the greatest challenges of your career so far?

Realising that you can’t be the best at everything. You have to chose a few specialities and work at them daily. Also learning the art of simplicity – not throwing every skill into one piece, ie checking the ego!

What are the special challenges/pleasures of adapting some of the legendary music scores from your father’s films?

Choosing which to arrange was the biggest challenge. Playing Vangelis my reharmonisation of his Chariots of Fire was another – luckily a successful one!

The pleasures include re-living the first time I heard each piece, getting into the nuts and bolts of them and hearing how they changed with my voice interpreting them, but keeping the essence of the wonderful originals. This is my thank you to all the kindness and generosity shown to a young me by all these composers.

What are the special challenges/pleasures of working with particular musicians, singers, ensembles or orchestras?

When you know which ensemble, orchestra or players you are writing for you can factor in their nuances. The joy is hearing a line you’ve written in your head, interpreted by a great musical actor. For Spirit of Cinema I had the pleasure of working with Magnus Johnson and Peter Fisher on solo violin, Roy Carter on oboe and Nancy Ruffer on flute, as well as multi-instrumentalist Richard Cottle, each of which brings their own musical accent to every turn of phrase.

Of which works are you most proud?

I’m incredibly proud of every track on my forthcoming album, but like every musician I’m now enthralled by my latest score for the documentary feature I’m working on about the life and work of the designer and architect Marcel Breuer, Breuer’s Bohemia and the music I’m writing for an Irish period drama.

How would you characterise your compositional language/musical style?

I touch on every style which as well as the classical – Plainchant, Baroque, Romanticism, Serialism and Minimalism – includes rock, pop and jazz, the grounding my training gave me. What I’m trying to do now, as I mentioned above, is simplify these elements into a cohesive style. I guess what I’m trying to say is after years of writing for different genres and films, I’m trying to distill all these elements into my own voice. It keeps me busy!

How do you work? What methods do you use and how do ideas come to you?

I try to listen intently (my wife might disagree) to my inner voice and the serendipity of what’s around me, but I find as I improvise on that idea I’ll catch a whisper, almost a scent of something which I chase that ultimately ends up being the composition, often somewhere far from the original inspiration. So improvising is my method.

Of course when I’m scoring for a director, I’m greatly influenced by their record collections and the sound they are looking for.

Who are your favourite musicians/composers?

Musicians, on the piano Stephen Hough, Angela Hewitt, Herbie Hancock, Alfred Brendel, Murray Perahia, Oscar Peterson, Keith Jarrett and I had the privilege of seeing Sviatoslav Richter performing in Moscow when I was studying there. Prince can’t be touched for overall musicianship – a superstar.

As for the list of composers, it’s too hard to name a few. It moves with the moment and the mood – as long as it’s heart not craft I’m all in.

Let’s say from Hildegard von Bingen to Hildur Guðnadóttir!

As a musician, what is your definition of success?

My definition of success as a musician is feeling I have finished a piece and I can put it down with confidence.

What do you consider to be the most important ideas and concepts to impart to aspiring musicians?

Use your faults and defects and plough your own furrow with confidence, and as Grayson Perry says ‘ Don’t get off the bus’!

What do you feel needs to be done to grow classical music audiences/listeners?

Finance lubricates the wheels of regeneration, putting money into music education is critical, making learning an instrument accessible to all, as well as subsidised tickets to see the professionals. Equally I would have radio stations stop filling the bulk of our airwaves with mainly dead composers. It is of course important to keep the old greats alive, however we must make much more space for the living and new.

Where would you like to be in 10 years’ time?

Living in the country with my wife with room for a grand piano, great friends and family, travelling to London to the premier of my latest movie score in a Covid-free environment!

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Putting down my pen at the completion of a composition. Michael Kamen always castigated me for using pen in my scores, not giving him the ability to rub them out. However my Russian teachers taught me that using a pen made your thoughts and instincts permanent

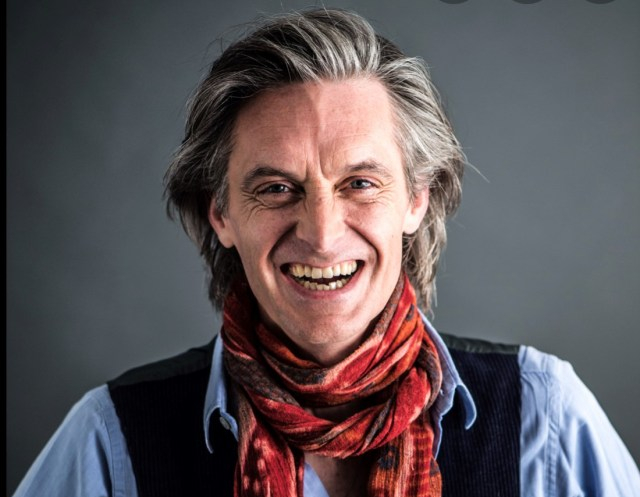

Sacha Puttnam (son of Lord David Puttnam and keyboardist in Bush) has released his brand new album Spirit of Cinema, which celebrates the iconic musical scores of his father’s multi-award-winning films through his sensitive orchestral and piano adaptions that bring a new and fresh perspective to these pieces.