Who or what are the most significant influences on your musical life and career as a composer?

Twirling madly around the living room in a home-made fairy dress age 2 to Tchaikovsky. Making elaborate costumes for my Sindys [dolls] and an exotic theatre space to house their dramas. Belly-flopping off the highest board in the Brownies’ diving competition. Poetry-reading contests, ballet classes. Full-body shivers hearing Bach’s St Matthew Passion for the first time.

On an NYO course, betrayed barely half an hour after my very first snog – seeing my beloved canoodling with the principal viola. Then rehearsing Mahler 6. Skiving off 6th form afternoons to weep in the bath for being fat, weird and unlovable. The gutter press headlines outing my teenage affair with the Headmaster…

The appalling boyfriends, the hideous break-ups, ecstatic wild partying, all-nighters reading, dancing, listening to every kind of music. Seeing Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters for the first time. Bribing a sullen Saturday music school quartet with wine gums. Being married by a high priestess of Isis on the island of Philae in Egypt to a random Dutchman for whom I sold my flat and gave away ALL my possessions.

Only to return home a year later, penniless.

Underworld assignations in the dead of night. Clubbing with champagne gays, oblivious to their shrieking mysogyny. Being able to do the splits. Greek island chamber music under a shimmering Milky Way. Hurtling off a Swiss mountain cliff edge on a child’s sledge – suspended over the void in a net.

All of it.

ALL of it, is part of the music that I’m now making..

There was never a point when I asked – what will I be when I grow up? Because being a musician is my essence. Not a career. And my job is to express that soul spark, in whatever form it takes.

In the innocent pre-times, my request to Jim’ll Fix It was to play a piano concerto with the LSO. On sweat-slippery keys, I worked through the standard Czerny, Chopin, Schubert, Schumann, Rachmaninov. Schoenberg blew my mind. Then followed the Herculaen task of trying to make the world’s most beautiful instrument – the cello – sound like a cello. Elgar, Walton, Prokovief, Henze, Debussy and Bach gazed on from the music stand.

Meanwhile, hiding in our strictly pop-free house-hold, brewed my life-long mania for funk, fanned by illicit viewings of Top of the Pops. FILTHY, glorious, grinding, bass-throbbing funk. I longed to be a Soul diva almost as much as I longed to be in the Royal Ballet.

And then quite suddenly, landing at university after an unbearable year of slow arpeggios and earnest flute-playing girls at the Royal College of Music – I met living composers.

I’d found my tribe.

More or less unguided, I attempted to decipher Ligeti, Xenakis, Sciarrino and Nono while learning scores still wet with ink. In the extreme cello-playing decades that followed, I laboured at the hardest of musical rock faces, playing music that right-minded people would cross town to avoid.

Months of brain-crunching, osteopath-paying effort went into each insanely difficult score, then performed to sparse audiences of angry beardy men in bad jumpers with worse social skills. Each time, attempting to breathe life into music deliberately divorced from feeling.

And yet, like particle physics, there was beauty to be found in all that theoretical complexity…

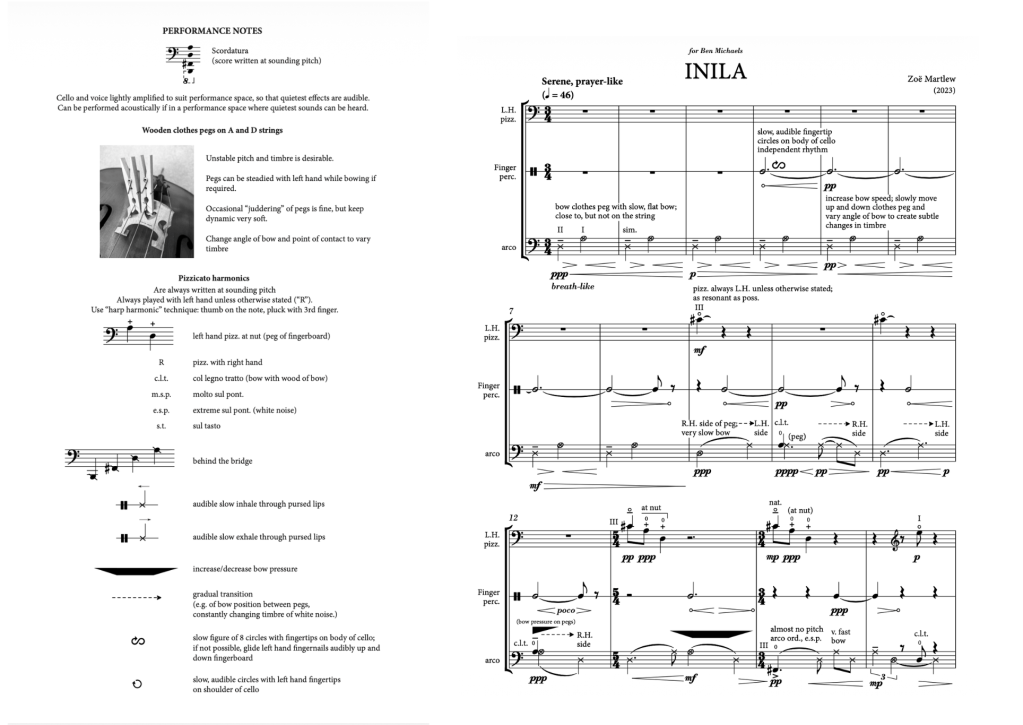

All those experimental techniques have come in super handy in my own work. Here’s a glimpse of a new piece for prepared cello, Inila. Bowing on clothes pegs sounds AWESOME – at times like a life-support machine…

Recording releases later this year, as part of an album of new cello works commissioned and played by cellist Ben Michaels.

One delirious afternoon – broke, with rip roaring tendonitis – I resigned from all nine of my contemporary music ensembles and decided to try out Everything Else.

There was the West End dep phase. Clocking my miserable expression following a double Les Mis day, the trumpet player gave me a sympathetic look.

“Don’t worry love”, he said. “The first sixteen years are the worst”…

There was experimental improv in Paris: scary French people in avant-garde smocks throwing ping pong balls into pianos. Experimental German dance theatre – IRCAM movement sensors, a stunt cello rolled in mud, outsize chef whites, nightly night full-cast onstage naked shower scene.

Amped-up backing girl for rock stars. Abbey Road session slut. Walk-the-gangplank improv terror for a silent Hitchcock film premiere at the BFI.

4am check-in at Luton airport with the RPO.

Masterclasses, award panels, university seminars. Working with sex offenders in a maximum-security prison; school kids with djembes; dreamers with saxophones, hope and a loop pedal.

Winding through it all were close friendships with countless composers – some of them amongst the greats. Quietly soaking up their vast knowledge of music through osmosis, love and alcohol.

My first serious experiments in creating my own music were kicked off by a collab with New York City Ballet dancer, choreographer and friend, Antonia Franceschi – writing music for her dancers, and Ballet Black.

“Shift, Trip” – written for Ballet Black, Linbury Studio, ROH.

Which led seamlessly into my one-woman cabaret show Revue Z – a mildly erotic experimental brew of my own music, comedy and theatre, glued together with multi-layered backing tracks.

The show’s tagline was – “Unhinged, uncensored, underwired” – a deliberate ploy to lure people into a new-music concert without quite realising.

I became like Harvey Keitel in Pulp Fiction.

The person you call when there’s an impossible problem to fix.

Then, in the blissful silence of that first lockdown, it all stopped. Adrenaline tap turned off for the first time since birth, every cell of my being soaked up that heavenly stillness, listening only to the sound of the waves and seagulls where I live.

The cello went firmly back into its case.

And then a miracle happened.

Commissions began pouring in for me to write for others.

G-lude.

The cathartic moment when I broke free from the chains of the cello.

What have been the greatest challenges of your career so far?

Where to even….

In one of her autobiographies, comedian Jo Brand speaks of the initation familiar to every stand-up: comedy death.

Mine came early in an outing of Revue Z at a theatre in Bath. Barely through the first number, horrified old ladies expecting Bach in a ballgown began walking out demanding their money back. Admittedly, I was dressed head to foot in S&M gear making pressure-scrape death-screech noises. But this was unexpected.

In a similarly mis-matched bit of festival programming, a man in glasses loudly cracked walnuts through the quietest, tenderest (to me) moment in the show. Pizzicatos triggered sniggers. My best killer gags met with stunned silence, a toddler whining for ice-cream at the back.

Challenges escalated as a judge on BBC TV’s Maestro.

Then there was the heart-stopping Proms hiatus – a frantic backstage search for a missing Barenboim – during which I was asked to give live BBC viewers an overview of Liszt’s entire symphonic output.

And then that two-minute ambush to define spectralism on Radio 3, and a live telly Newsnight face-off with Michael Portillo on music education.

Me on BBC Proms interval chat:

Especially high on the challenge list:

Looking after needy, difficult men.

Getting through airport check-ins with a cello.

Being Artistic Director of the Saigon Chamber Music Festival – curating and coaching music for a bunch of live-wire 13 – 29 yr olds of wildly differing standards, all instruments (mostly intact) in 35 degree heat, fuelled by caffeine, idealism and a finely honed sense of the ridiculous.

Being asked to deliver a lecture on contemporary classical improvisation techniques to a packed hall of expectant Vietnamese parents, in front of a live TV crew, in the dripping heat of a Saigon afternoon – at zero notice.

Lying on my back strapped to the floor somewhere in Denmark for a four-hour video shoot: red ropes hooked to my dress, lip-synching over and over to Red Room, a brothel song I’d written – mascara running, dignity negotiable.

Then things got colder.

Trying to marshal a small army of beginner string players and their parents, working from phrase-book Norwegian on Sámi National Day in a town somewhere above the Arctic circle – cello cracking with cold.

Listening to the harrowing stories of the extraordinary young musicians of the Palestinian Youth Orchestra in desert-heat Jordan, then hearing them make their own music with a fierce, defiant joy and heart-wrenching beauty that is now burnt into my soul.

And the hardest of all:

being faced with a blank piece of manuscript paper before committing to that first note.

No longer hiding behind the creative projects of others, but fully and entirely committing to a vaster field – that of unborn sound itself.

What are the special challenges/pleasures of working on a commissioned piece?

Each commission has it’s unique coordinates to uncover – the artists, the instrumental and/or vocal line-up, the performance context, the venue, the people, the stories behind it all.

And, that all-important and unavoidable thing – the deadline.

I know from bitter experience on the other side of the music stand that late scores derail performances – and the blame nearly always lands on the performer.

NOT ON MY WATCH.

Deadlines are like bras.

Sometimes uncomfortable, occasionally restrictive, but essential for support, shape and avoiding overspill.

The commission theme here was Hildegard von Bingen. Preparing the piece sent me deep into the origins of her mysterious “unknown language” – and into the Abbey itself. I dedicated the work to the Abbess of this living Benedictine order.

As a relative newcomer in terms of writing for others, there’s also the particular challenge – and pleasure – of learning new instruments and combinations.

Having played countless premieres – and dernieres – of pieces appallingly written for my instrument, I absolutely refuse to give other performers anything that doesn’t work, and make sure I’ve done my homework.

There was writing for heavy metal band:

A one-minute YouTube organ-writing challenge – which unexpectedly revealed that, along with my Dad, five great uncles and five great aunts ALL played the organ.

The harp is next on the work bench. A dreaded initiation for many composers, and frustration for harp players who constantly tell composers to put on their big girl harp pants and sort it out already.

Am rather looking forward to going down this heaven-approved sonic rabbit hole.

What are the special challenges/pleasures of working with particular musicians, singers, ensembles or orchestras?

Probably because of my performer background, I’ve been unusually lucky to know almost everyone I’ve written for so far – and when I haven’t, I always make contact before starting on the notes.

Each performer or ensemble has a distinct energetic signature. I love getting under the skin of their sound world and psyche, and try to write music they actually want to perform – music that brings out the very best of who they already are.

A good example is Atma – for clarinet and electronics – written for Mark Simpson. I knew he could inhabit the theatrical vocal and breath-driven effects the score demands, while still carrying long lyrical arcs with real emotional intensity.

For singers and solo instrumentalists I’ll often start by asking a few simple questions:

what are your money notes? Your favourite register? Favourite sound colours? And then I listen to a bunch of their recordings for further insights.

Because a happy performer means a happy performance. Not to mention the chance that they’ll want to do the piece again.

Which absurdly, so rarely happens in new music. All that effort – and one show?

No thank you.

Another happy collab example was writing song cycle In the Park for tenor Alessandro Fisher and pianist Lana Bode. Alessandro’s miraculously beautiful voice, held and shaped by Lana’s exquisitely refined playing – both giving their all to explore the expressive possibilities of each song – was pure creative joy. This kind of collaboration is beyond precious.

Here they are on transcendent form:

“In the Kyoto Garden”

Of which works are you most proud?

I’m thrilled to bits to have just launched an album as a composer – Album Z (NMC Records) – a collection of works written for an outrageously stellar group of performers, all friends and colleagues who commissioned the pieces.

Listen to the full album here:

Streaming – https://NMCRecs.lnk.to/AlbumZ

I’m particularly fond of the two electronic pieces on this disc – a medium that gives scope for the otherworldly cosmic drama I’m drawn to. Alongside Atma, mentioned above, there’s Nibiru, an apocalyptic space drama written for the phenomenal Ben Goldscheider.

At the other end of the spectrum, I had a ball creating soprano-harpsichord triptych The Enchanted Garden for Anna Dennis and Steven Devine. Premiered as part of a sound installation for medieval Ightham Mote, the piece drew on paintings by Brazilian artist Ana Maria Pacheco, exhibited alongside it – and set some sexy texts from the Song of Songs.

The Enchanted Garden

Right now, I’m hugely excited about the upcoming release of my thirty-minute Faustian romp through the seven deadlies – Hôtel Babylon – a drama in seven scenes using my own texts, with soprano Claire Booth and pianist Jâms Coleman absolutely SLAYING it. It was a HOOT to write – pure theatrical fun – and I can’t wait to see it out in the world, fully lit.

But you know what? The music I’m most proud of lies ahead.

In the pipeline are two genre-bending vocal-and-ensemble theatre works with electronics; a new piece for oboe super-power Nicholas Daniel (also with electronics); a string quartet; and my answer to Britten’s Serenade for tenor horn and strings.

How would you characterise your compositional language?

Music that moves between worlds

Theatrical, dramatic, highly coloured.

At the moment – more or less impossible to categorise.

Make ‘em laugh, make ‘em cry – that’s probaby what drives me. In other words – music that connects: through humour, storytelling and harmony.

The notes really matter to me – harmonic worlds, rhythmic drive, clear sonic colour palettes – used for precise shaping of atmosphere and character.

How do you work?

The commission arrives.

In pretty much every case, an idea instantly lands in my body as a kind of energy ball – a complete world, still unmanifest in form, but already carrying the piece’s character. A blue-print, waiting to be decoded.

First comes a long walk by the sea: notebook in hand, muttering and humming, a mad middle-aged bat in wellies and no make-up.

Back at home I dance, move and sing the piece into existence, writing out the words, shapes and progressions of ideas in my latest black Moleskin.

Then I draw the structure -– visual sketches in lines, swirls and dots.

I decide on the pitch and rhythm DNA key from which the forms will grow, and write it out. The key chart also gives permission to sway from it, should the piece decide it doesn’t like the rules.

I keep my instrument/voice charts close to hand – checking pitch ranges and money notes (as discussed earlier).

Then the rituals begin:

sharpen Blackwing pencils.

replace rubbers in my Staedtler mechanical rubber thing.

tack manuscript paper to the architect board above the piano keyboard (yep – it starts analogue)

post-it notes at the ready.

Fall into the heavy sleep of procrastination.

Wake.

Repeat.

As a musician, what is your definition of success?

Giving your all to whatever project is in hand – doing your absolute best in the moment with all your being, no matter what the outcome.

And even when it looks like total disaster from the outside, keep going anyway.

What advice would you give to young/aspiring composers?

Have faith in your own ideas.

Even when – especially when – they directly clash with what you’re told is “correct”.

Music that wins competitions or earns you a PhD isn’t necessarily true to your voice.

ALWAYS check your instrumental writing for practicality.

Don’t write tricky extended techniques just because you learnt them in a workshop.

Performers are SOOO tired of pointless difficulty.

Every effect should have a musical reason.

Present your work impeccably

Given the woefully short rehearsal time usually allotted in the UK, clear, elegant engraving matters. Legible parts and scores save precious time – and goodwill.

Ridiculously impractical parts full of errors get dismissed fast. A streamlined, professional-looking score gets everyone on your side– and lets you get straight to the music in rehearsal.

What do you feel needs to be done to grow classical music’s audiences?

TALK to them.

I’ve sat through endless concerts where audiences are somehow expected to already know what’s going on on stage. For someone who’s never been to a classical concert before, it can be utterly bewildering.

A clear, friendly, informative – but not dumbed down – spoken intro is essential. Just enough context to give listeners something for their ears to hang onto. And while we’re at it: let people know, clearly and simply, what’s expected with the clapping thing.

If pop, rock, folk and jazz concerts can manage it, then so can classical.

(It also helps if the MC has a sense of humour.)

Programmes

Almost no one reads them. And if they do, it’s usually during the concert – which means they’re bored, confused, or stuck in their heads instead of listening. Digital programmes are even worse: encouraging already screen-saturated audiences to look at their phones during concerts is new music suicide.

With contemporary music in particular, programmes need to be curated, not just assembled. Vary the menu. Think in terms of colour, contrast and pacing. Not back-to-back new works that leave everyone’s ears scrambled and spirits depleted.

Lighting

Good lighting makes a vast difference. It helps smooth transitions, supports the emotional flow of an evening, subtly shapes atmosphere and allows the audience to feel held rather than abandoned between pieces.

Space

As long as the acoustics support the music, I’m all for performance spaces where audiences can move, stretch and breath – rather than sitting bolt upright in rigid rows. Let people experience sound in their bodies, not just in their heads

What’s the one thing in the music industry we’re not talking about but you think we should be?

Child care.

Its absence is written plainly into the still male-dominated composer stats.

You simply cannot compose when a small child is demanding your attention. More than almost any other art form, composition requires Virginia Woolf’s room of one’s own – preferably a quiet one, without interruption.

How freelance musicinas with children cope is honestly beyond me. There is virtually no structural support. People are battling insane diary logistics, last-minute work, strange hours, touring, unstable income – often paying to work. It’s brutal on relationships, and BEYOND exhausting.

Single mothers who are creative musicians are the quiet powerhouses of our age. What they manage is nothing short of superhuman. I’m in awe.

There are people finally flagging this enormous white elephant – notably, soprano Hannah Sandison and SWAP-ra (Supporting Women and Parents in Opera) – but the conversation is still nowhere near loud enough.

Even without kids it’s hard enough to keep going as a musician. How muso parents manage at all is a genuine mystery.

What next – where would you like to be in 10 years?

To be completely at peace, regardless of the outer situation.

To have grown – as a composer, and as a human.

Assuming the planet still exists, to have the musical and technological tools I dream of, and the freedom to build the theatrcial sound-worlds that already live in my head.

Writing large-scale theatre works that are tourable, affordable, outrageous and full of life – for all kinds of audiences, in all kinds of places.

Making music that brings comfort and light in turbulent times

To have a strong, happy bod.

That, and the ability to make Ottolenghi recipes from memory. On demand.

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Oneness with All That Is.

And swimming with turtles in Kauia

What is your most treasured possession?

My health

What do you enjoy doing most?

Being out in nature – preferably by the sea.

What is your present state of mind?

Feeling incredibly blessed

Zoë Martlew’s debut album Album Z is out now on the NMC label. Find out more

Discover more from MEET THE ARTIST

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.